This is a refreshed version of the post I made on 9 January 2024. Some content is the same, but I would like to think I have made the overall argument stronger

Weller’s (2014) account of the history of open learning highlights how the free and open source software movement formed the inspiration for creative commons and therefore possibilities for open educational resources. However, it concerns me that this connection is overlooked when phrases like “open technologies” (Weller, 2014, p.94), “open tools” (Cronin, 2017, p.8) and “open online spaces” (Perryman, 2023, Step 2.13) are used. In these contexts, the word ‘open’ conveys the idea of being outside of the physical and virtual boundaries of an educational institution, rather than the licensing of the software.

Examples of open educational practices (OEP), such as the use of Twitter [now X] (Weller, 2023), link the practices with Big Tech’s “killer apps” which have been associated with data exploitation and neglect of privacy amongst other abuses (Fowler, 2021). The Thesis Whisperer (Mewburn, 2023) has already highlighted that the “enshittification” of social media means that academics should accept that they are now useless as communication tools to raise personal profiles or create research impact. Authoring blogs and developing email lists can be more fruitful.

I do understand that practices like microblogging and sharing photos and videos can be attractive to open educational practitioners interested in sharing educational resources and blurring the boundaries between formal and informal learning. However, I do think we should be ethical in the choices we make about the types of technologies we choose – and influence (or ask) others to use. Resources for educators (for example, Ritter, 2021; Salmon, 2014) ignore ethical considerations in their guides on using social media services for different educational purposes. The only nod to ethics I have been able to locate is the inclusion of Security and Privacy as the final S in the SECTIONS model designed to help inform the choice of technology (Bates, 2022, section 10.9).

This really troubles me. Shouldn’t we be aware of the impact of our choices? In addition to considerations of reach and accessibility, there are three important distinctions that I think should inform our choices.

- Centralised social media services vs federated social media services

Centralised social media services are those that are run by a single organisation (Flatline agency, no date). The single organisation controls how the service is used and experienced, for example they can decide how much can be viewed without setting up an account and users’ terms and conditions. They also decide on charges for premium accounts or accessing content en masse via an application programme interface (API). The dominant social media services are centralised and run by Big Tech companies, such as Meta, X and Google.

In contrast, federated services can have multiple organisers and service providers. The most widely used federated service is email – this is why it is possible to send and receive emails with people who use different internet service providers. There are also a set of interconnected social platforms enabling microblogging, photo and video sharing – this is called the Fediverse. A short animation is available on Fediverse.info. It explains the downsides of centralised services and the benefits of federated services. It uses the idea of different planets to represent each service provider. With centralised services, you can only communicate with people on your own planet, with federated services there are protocols in place so that you can communicate with people on different planets. It all works on an open protocol called ActivityPub which is maintained and recommended by the public interest, non-profit World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

But there are some blurry lines here.

For example, very recently Meta have caused controversy by incorporating ActivityPub into Threads. This means that users will be able to choose to follow Threads posts from other federated services like Mastodon or PeerTube. However, in choosing to ‘follow’ one or more Threads accounts, you may still need to sign up to a whole tonne of terms and conditions decided by Meta. So sadly, it is possible for centralised, big tech to try and exploit the fediverse and catch out unaware users.

Another example of a blurry line is the recent introduction of the AT protocol which effectively competes with ActivityPub by opening up the potential for a completely alternative universe of federated services. The protocol is developed and maintained by Bluesky, a US based for-profit, public benefit company. The first application that implements this protocol, Bluesky, is gaining popularity.

- Proprietary vs free (libre) vs open source software

Comparisons can be drawn between software licenses and licensing used for other creative works. A proprietary license is the equivalent of full copyright (Wikipedia, 2023a) and is usually closed source in that the code is not released to the public (Wikipedia, 2023b). Most Big Tech centralised services are proprietary.

In comparison, open and free licenses grant different rights to users in the same way that different forms of creative commons licenses do (Wikipedia, 2023a). The terms ‘open source’ software and ‘free (libre)’ software are often used interchangeably or together in phrases like ‘free and open source’. However, free software is based on a full set of freedoms – the right to run the software, “change and study it, and to redistribute it with or without changes” (Stallman, 2022). It is like the least restrictive creative commons license (CC-BY-SA). Furthermore, free (libre) software associates itself with a set of ethical values such as freedom and justice. Mastodon, Pixelfeed and PeerTube all have free (libre) licenses.

As Stallman (2022) explains, open source licenses may restrict one or more of the freedoms reflecting some sort of middle ground. An example is Bluesky – the application code is licensed under an MIT license which is officially an open license, but only just – it allows commercial use and there is no ‘Share Alike’ requirement.

Many people are not always this precise when they use the term ‘open’ and, as Masson (2014) outlines, companies do engage in ‘openwashing’. This means you really do have to dig to identify how source code is actually licensed.

- Commercial vs non-profit services

In the UK television comedy quiz ‘Would I lie to you’, comedian David Mitchell is asked to convince other contestants that he does not use WhatsApp. When one of the other contestants points out WhatsApp is free, he responds “That’s what they say then isn’t it, if it’s free, you are not the customer, you are the product” (BBC, 2023, 02:20).

According to Quote Investigator (2017), the point was initially made about commercial television in the 1970s. Let’s face it, ads are annoying – especially when trying to watch an online lecture on Google’s YouTube. But, the problems run deeper with online services, given the potential for data harvesting, algorithm-driven ‘personalisation’ and bot-driven feeds. It has been identified that these practices are not just used for influencing purchasing choices but manipulating and shaping culture and politics (Gray, 2023; Hodge, 2019; Taylor, 2023).

There are some possibilities that some users could avoid these problems. Writing in 2017, Kulkarni predicted that social media services could introduce different payment tiers to allow users to pay for an ad-free level of service. This could help those users who can afford to pay but creates an inequitable experience which clash with the values of open educational practice. More recently, the 2023 European Union (EU) Digital Services Act introduced a requirement for social media services to include features to allow EU users to select algorithm-free feeds. In some cases, social media services have opted to introduce these features globally (Lomas, 2023) but this is not guaranteed. Countries in the Global South have less power to introduce regulation against disinformation (Takhshid, 2022), which raises the potential for different exposure to disinformation and algorithm-driven campaigns in different parts of the world.

In contrast to the commercial model, there are some social media services that are run by non-profit organisations and are funded by user donations, sponsorship or grants. These services are committed to avoiding advertisements and algorithms. An example is Signal Messenger, run by the Signal Foundation – a non-profit that champions user privacy.

So, what I hope is that open educational practitioners, supported by educational institutions, will start choosing non-profit over commercial, federated over centralised and free(libre) wherever available. I see these as more ethical choices because we aren’t expecting those who want to learn with, and from, us to be subject to the abuses associated with centralised, commercial services. I call this ‘open squared’.

How hopeful am I that my future will be realised? I was pleased to see that I wasn’t the only person studying H880 23B who was avoiding the main centralised social media platforms. This suggests I am not the only educator seeking alternatives.

I was also given hope by an example from the Netherlands – there, a number of universities have grouped together to set up a Mastodon instance for staff and students (Ad Valvas, 2023). By creating their own instance, they can decide on the rules for use of their service by staff and students, But, the interaction between Mastodon services, and other fediverse apps such as PeerTube and Pixelfed, will enable their users to participate in discussions and use resources elsewhere in the fediverse if they want to.

Imagine if this happened here in the UK or even was something taken forward by the Open Universities of the world. How good would that be?

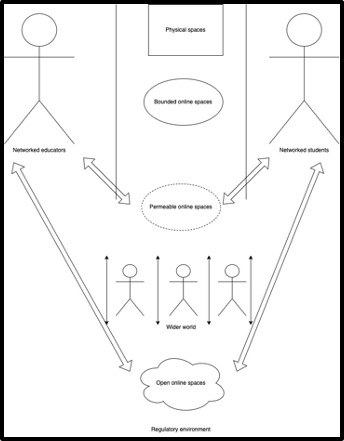

It would offer a new space that could be inhabited by educators and learners which I think of as permeable online spaces. These would be managed by educational institutions with local usage policies, but allow federation with other instances and servers for interactions with the wider world. I represent this in a diagram adapted from Perryman (2023) below.

Figure: Representation of the type of spaces that could be inhabited by educators and learners in the future

Figure: Representation of the type of spaces that could be inhabited by educators and learners in the future

Acknowledgements

The diagram, “Possible future spaces”, is adapted from “Representation of the types of spaces inhabited by educators and learners” by Perryman, 2023, adapted from Cronin, 2013, adapted from Courous, 2008, used under CC-BY-SA-NC 2.0 | addition of permeable online spaces

With thanks to the class of H880 2023 whose discussions inspired and shaped my thinking about open learning and social media.

References

Ad Valvas (2023) Universities create their own bubble on Mastodon. Available at: https://www.advalvas.vu.nl/en/nieuws/universities-create-their-own-bubble-mastodon (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Bates, A.W. (2022) Teaching in a digital age: Guidelines for designing teaching and learning, Third Edition. Available at: https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/teachinginadigitalagev3m/ (Accessed: 1 August 2023).

BBC (2023) David Mitchell rants about WhatsApp for three minutes | Would I lie to you? Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjCzkzYaFlg (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Cronin, C. (2017) ‘Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education’, International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). Available at: https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096.

Fediverse.info (no date) What is the fediverse? Available at https://fediverse.info/ (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Flatline agency (no date) What is decentralized social media? Pros and Cons. Available at: https://www.flatlineagency.com/blog/what-is-decentralized-social-media (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Fowler, S. (2022) Big Tech’s Dark Side: Killer apps, abs, and acqs. Available at: https://poole.ncsu.edu/thought-leadership/article/big-techs-dark-side-killer-apps-abs-and-acqs/ (Accessed: 7 October 2023).

Gray, C. (2023) Algorithms are moulding and shaping out politics. Here’s how to avoid being gamed. Available at: https://theconversation.com/algorithms-are-moulding-and-shaping-our-politics-heres-how-to-avoid-being-gamed-201402 (Accessed: 4 October 2023)

Hodge, K. (2019) It it’s free online, you are the product. Available at: https://theconversation.com/if-its-free-online-you-are-the-product-95182 (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Kulkarni, C. (2017) 11 ways social media will evolve in the future. Available at: https://www.entrepreneur.com/science-technology/11-ways-social-media-will-evolve-in-the-future/293454 (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Lomas, N. (2023) All hail the new EU law that lets social media users quiet quit the algorithm. Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2023/08/25/quiet-qutting-ai/?guccounter=2 (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Masson, P. (2013) Openwashing: adopter beware. Available at: https://opensource.com/business/14/12/openwashing-more-prevalent (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Mewburn, I. (2023) The enshittification of academic social media. Available at: https://thesiswhisperer.com/2023/07/10/academicenshittification/ (Accessed: 8 February 2024).

Perryman, L.-A. (2023) ‘Opening up education’, H880 Technology Enhanced Learning: Foundations and Futures. Available at: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/h880-opening-up-education/5/todo/162412 (Accessed: 7 October 2023).

Quote Investigator (2017) You’re not the customer; you’re the product. Available at: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2017/07/16/product/ (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Ritter, K. (2021) Selecting the right EdTech tool. Available at: https://talktechwithme.com/resources/selecting-the-right-edtech-tool/ (Accessed: 1 August 2023).

Salmon, G. (2014) Social media for learning design. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRX8d6cFoFI (Accessed: 7 October 2023).

Stallman, R. (2022) Why open source misses the point of free software. Available at: https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/open-source-misses-the-point.en.html (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Takhshid, Z. (2022) ‘Regulating social media in the Global South’ (Abstract), Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law, 24(1). Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol24/iss1/1/ (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Taylor, J. (2023) Bots on X worse than ever according to analysis of 1m tweets during first Republican primary debate. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/sep/09/x-twitter-bots-republican-primary-debate-tweets-increase (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Weller, M. (2014) The battle for open. London, UK: Ubiquity Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5334/bam.

Weller, M. (2023) ‘Week 4: Open now’, The Online Educator. Available at: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/the-online-educator/16/steps/1673400 (Accessed: 7 October 2023).

Wikipedia (2023a) Proprietary software. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proprietary_software (Accessed: 4 October 2023).

Wikipedia (2023b) Comparison of open-source and closed-source software. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_open-source_and_closed-source_software (Accessed: 4 October 2023).