The other evening, I went out with a colleague and friend of mine – T. Well I say colleague, we used to work for the same organisation – now we work for different organisations but within the same partnership arena. When we worked together, we routinely had a friday night drink during which we discussed society, organisations, management and so on – at the time he had just finished a social policy PhD and I was embarking on my MBA.

It’s been a while since we have seen each other outside formal meetings. In our conversation the other evening, we started talking about complexity. T has an emerging interest in the complexity of individual’s lives and the tension created when organisation’s have to be accountable for the ‘outcomes’ they achieve through their interventions. Entire voluntary sector funding regimes are founded on organisations making claims for the outcomes they can create.

Contemporary public health research has an underpinning systems perspective. The most reproduced model is that by Dahlgren and Whitehead which shows a series of influences on the health and wellbeing of an individual. In Newcastle upon Tyne, I have been involved in work to raise awareness of this ‘holistic perspective’, most notably with our Mythbuster brochure.

What my discussion with T made me realise, is that to date, I have not seen health theory expressed using the language of Systems (the academic/intellectual discipline). So here is my first iteration…

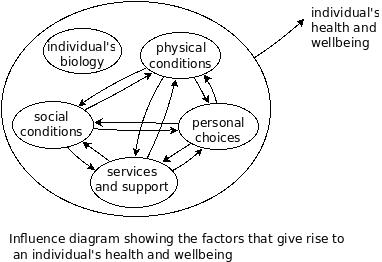

An individual’s health and wellbeing is an emergent property of the interactions between the individual’s biology; the physical and social conditions in which they live; the personal choices they make; and, the services and support they access.

The influence diagram below illustrates this:

What are the implications of this for what I do?

The primary concern in my work is how this plays out at a population level. The way our society is structured means that some communities of identity, interest or geography will experience poorer physical and social conditions, be less likely to access services and support, and be less likely to choose health and wellbeing enhancing behaviours. In short, inequalities in health – such as that measured through shorter life expectancy in ‘deprived communities’ – are the unintended consequence of the way in which our society is structured.

..and for T?

Back to T – as someone who works in the voluntary sector he is required to fill out application forms that state the outcomes he will achieve for the people who use the services of his organisation. His primary concern is therefore how this plays out at the level of an individual – or aggregated up to a customer group.

The term outcome has seemed to gain in profile as we all tried to get away from measuring inputs, outputs and getting caught up in processes. Outcomes now seem to be mentioned everywhere and in many different guises and ways. In essence, they are all about how we value or evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention.

In Newcastle, we have adopted a framework known as Outcomes Based Accountability which defines outcomes as “conditions of wellbeing”. I find the framework useful in creating a shared language and way of planning. I think of the formally stated ‘outcomes’ as entry points for describing and improving wellbeing, but there is a tendency for people to use them as if they are isolated programmes of action.

Anyway, the point of saying all this is that ‘outcome’ is essentially performance speak for wellbeing. So I can re-state my sentence above – outcomes are an emergent property of the interactions between the individual’s biology; the physical and social conditions in which they live; the personal choices they make; and, the services and support they access.

In claiming that a particular intervention will create a particular outcome for its customers, T is put in the position of claiming a linear chain of causation between the intervention and the outcome. But, he knows that peoples’ lives are more complex than that – that there are other factors at play.

Mark Friedman, the founder of Outcomes Based Accountability (in US it is referred to as Results Based Accountability), has done recent work on Next generation commissioning which does go a little way to getting over this anomoly – he says that funders can ‘buy’ quantity and quality of service but can only expect the funded service to work with them to achieve certain outcomes. I guess this is in recognition that often a network of services is needed to create outcomes rather than an individual service. But still however, this seems to assume that outcomes are the result of interventions by services – not the broader set of factors in my influence diagram above (or we could be assuming that all the other factors have remained static?).

Furthermore, T talked to me about the narratives of people’s lives – how what professionals define as desirable outcomes are not necessarily experienced that way by ‘service users’.

I guess what I am left with at this stage is a question of how to evaluate the difference an intervention makes to an individual’s wellbeing. Outcomes were a step-change over the old ‘outputs’ model. How can we use systems principles to take this one-step further?

Excellent summary of our discussion! I love your health diagram – mind if i borrow it for my paper on the complexity of outcomes?

T

Hi T – glad you liked it.

course you can – but I am sure my ideas will develop now you have triggered this chain of thought – maybe we’ll need another evening out once you start writing it!

H

Hi Helen

Loved this blog – Whilst I am not as engage as yourself in the health agenda the point on how we manage/negotiate/build the gap between professionals definition of ‘outcomes’ and the individuals definition in a meaningful way is an area I wrestle with in other spheres on a daily basis – Perhaps one way of exploring this is though looking at to ‘recursion’ between the different domains and our different meta-narratives?

As a side question I am interested to know why in your diagram you choose not to put a link between ‘individual’s biology’ and the other area?

Hi Bridget

Thanks for your comment.

I saw T again at the weekend and I think this train of thought is going to keep on developing. We are so used to seeking ways of quantifying the achievement of outcomes but as localism kicks in how can we pick up non-numerical ways of picking up the community’s real narratives and stories.

The individual’s biology issue has been vexing me since I blogged this. By biology, I mean genetics and age, which are not influenced by the other factors. However, does your genetics influence your personal choices or services and support you receive – I’m not sure. There is evidence that men are less likely to use health care services – but is that is probably more institutional than ‘pure’ genetics. Be interested in your thoughts.

Helen

Pingback: Just Practicing − The use and abuse of measurement

Pingback: Just Practicing − Outcomes

Pingback: Just Practicing − Conceptions of wellbeing