I’ve just been reading a book that draws on the work of Wittgenstein to state:

“He [Wittgenstein] maintained that there are two main kinds of problem: problems of ignorance (there are things existing that we do not know enough about and therefore we require more information), and problems of confusion (we have the information but we do not understand what it amounts to).”

Hart (1998, page 141)

This got me thinking…

Problems of ignorance seem to govern a lot of how we (people in public sector) spend our time. We are either giving information or asking for it continually. Whether it is information about ‘need’, information about policy, information about ‘what works’, information about what we are actually currently doing and achieving. Problems of ignorance require time and skills to research, aggregate, present and disseminate information – mostly quantitative, sometimes qualitative. They are skills we have and a lot of a ‘policy officers’ time is spent doing this sort of work.

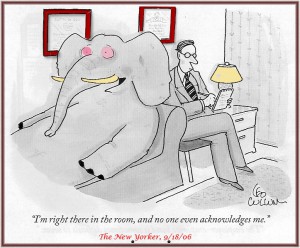

Problems of confusion, on the other hand, are not only given very little time – they are also rarely acknowledged. They are in short – the elephant in the room.

Resolving problems of confusion requires mental activity – i.e. thinking. Problems of confusion don’t get resolved by a ‘two page brief’ or a ’10 minute presentation’ – but they can begin to be unraveled through a humble attitude and a learning, inquiring orientation. It is about reading for learning, reading for inspiration, analysis, synthesis, discussing with others and learning from their perspectives, dialogue and social learning. However, because confusion isn’t acknowledged, we think it is ignorance – we ask for more information, more briefs, more presentations. (Hence absorbing even more of policy officers’ time)

But I’d like to add a third ‘problem’ to Wittgenstein’s list – which I call problems of confidence. It doesn’t matter how much we act to reduce ignorance and confusion, in a complex, dynamic world, there will always be ambiguity and uncertainty (they are the elephants in the world of policy!). By the time we understand something, it will have changed. If we seek ‘perfect information and understanding’ before we act, we will never act. So ultimately, we also need to be able to tolerate uncertainty and ambiguity and do what makes sense or feels right – including what feels morally or ethically right – even if we are not certain of what impact that action will have. In my experience, confidence comes most of all when you are working with others – if you’ve been through the experience of reducing ignorance and reducing confusion together – the shared understanding and ‘checks’ from different perspectives are the foundation you have to act from.

Reference

Hart, C. (1998), Doing a literature review: releasing the social science research imagination, London: Sage Publications.

A very insightful. My take on your comment would be that there can only ever be partial knowledge particularly in open and dynamic systems.

Note to self: is there a fourth type of problem? I shall call it the ostrich problem – where there is the information (or evidence) but it is too difficult to take into account because it contradicts the ‘easy’ route or your default way of doing things. So you ignore it, pretend it’s not there.

In my view, the ostrich problem is a question of professional integrity and ethics – if the information you are ignoring is about issues that may affect another person’s wellbeing and health, then you are affecting their right to positive wellbeing and good health.

Medical practice does try to keep up with new evidence about wellbeing and health, but do managerial practitioners or policy practitioners really dare to understand the impact of what they do or don’t do – even though the evidence is there?

That’s a very interesting point with regard to ethics – it reminds me of something I once read, that more often than not, it is easier for us to change our beliefs and values than change our behaviour.

Reflecting on your earlier entry as well that resolving problems needs mental activity, the need for multiple perspectives and time to think – reminds me of the issue that problems too are shaped by our worldviews to some extent, exemplified by the story/stories of the Blind men or blindfolded and that elephant ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blind_men_and_an_elephant )- i.e, that we all see only parts of the whole. Sitting too in our offices and trying to absorb all the information, prevents us from developing understanding of the whole, by engaging in the situation with other stakeholders. Does that make some sort of sense?

Hi Philip

not just the elephant in the room, but the blind men and the elephant.

Interestingly I recently opened a presentation on ‘Measuring wellbeing'(for a workshop at work) with that very story-line…and also made the point about ‘being out in the swamp’ (rather that on the technical high ground). You may be interested in the presentation. It’s at http://www.wellbeingforlife.org.uk/measuring-wellbeing-and-changes-wellbeing-newcastle

(it was my way of trying to open a workshop in a way that made people debate rather than just take measurement for granted).

regards

Helen

great I’ll check that out for sure.

That’s a great presentation Helen! Really good. Looks like you were able to draw on a lot of your studies in STiP. How was the reaction to the presentation? Would have been interesting to be a fly on the wall.