In public health, the notion of behaviour change has been around for a while. The focus stems from the desire to reduce or eliminate ‘health risk behaviours’ like smoking or alcohol or to introduce ‘health enhancing behaviours’ like physical activity or nutritious diets. There has been plenty of research by health psychologists to explain how behaviour change happens (descriptive theories) that are now being used to design interventions (turning them into prescriptive theories but that’s another matter).

But that’s not what I want to focus on – there has been this odd creep of phrases like ‘behaviour change’ into the language of leadership and management. It seems not only do leaders and managers need to ‘change their behaviour’, they also need to know how to change that of their ‘subordinates’. I’m all for seeing how helpful ideas can be when you transfer them across disciplines but I feel very uneasy about this transfer.

The word ‘behaviour’ makes me think of Pavlov’s dogs – something that happens as result of a stimulus. It also makes me think of small children who have ‘bad behaviour’ that need to sit on the naughty step. Used in a leadership/management context, it evokes a parent-child relationship and an action that is a reflex rather than consciously taken. In fact the more I unpick it the more I dislike the fact that it is used in public health too – it doesn’t seem too far from clinical notions of behaviour modification and the state mass ‘control’.

Personally, I prefer to think about ‘developing our practice’ – Ison (2010) talks about a practice as being any verb – managing, leading, understanding, supervising, appraising, communicating, writing, enabling, measuring, monitoring and so on. He provides a heuristic to help unpack the dynamic of practice.

I’ll attempt to explain what this means to me.

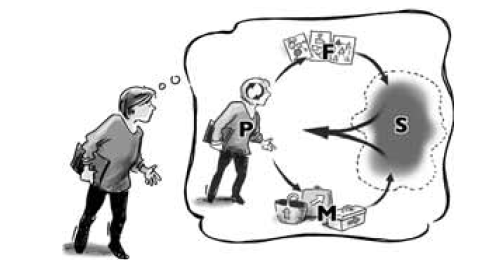

At the centre we have a practitioner (P) – the person with rich experience and background that gives them a unique perspective on the world. The practitioner is part of a situation (S) – the situation is something they want to improve, for example organisational culture or a city’s wellbeing and health – and that situation is packed full of people that they need to relate to (either singly or en-masse). The practitioner needs to be purposeful – to make aware choices about how to engage with the situation. This shouldn’t be a ‘behaviour reflex’ those choices can be consciously made (that’s what makes us human).

The practitioner draws on two elements to engage with the situation. Firstly, their framework of ideas (F) about how the world works and how the situation operates – these ideas are a set of theories, some of which may have been formally developed and learned but many will be tacitly developed and held. These theories – whether the practitioner knows it or not – are value laden. Like a pair of goggles, they also affect the way the practitioner perceives the situation. For example, a theory that ‘the world is a problem to be solved’ will lead to a different perspective and way of engaging than thinking ‘the world is a situation I need to act to improve’.

Secondly, in engaging with the situation, the practitioner will use ‘methods’ or ‘tools’ (M) – in management we use tools like SWOT analysis or GANTT charts or appraisal forms or action plans. In policy work we use methods for ‘assessment’, ‘engagement techniques’ and for designing good conversational spaces. These methods have embedded into them assumptions (theories) about how the world works. For example a GANTT chart assumes that the world is predictable and certain and that you know the destination before you start the journey – therefore for some situations it is the right tool, for other situations – particularly where learning is required – it isn’t.

Reflective practice is about being able to stand back – preferably in the moment of doing to consider what it is you do when you do what you do? What is it about your framework of ideas that is affecting how you are working with the situation? What is it about the methods you are using that give them strengths and weaknesses? What are the choices you are making in that moment about theories and methods and how are they affecting the way you are dealing with the situation? Could additional, different theories and methods offer a richer understanding of the situation or provide different opportunities for improving it? Becoming aware of this, in the moment, is likened by Ison to a juggling act – I’ve covered these before in a number of posts, such as What do I do when I do what I do revisited and A reflection on juggling.

Developing practice – to me – is about widening your repertoire of ‘framework of ideas’ and of ‘methods’ (and getting better at the juggling). This isn’t a replacement of your old repertoire you always have them to draw on if you choose to. It’s particularly important to be able to understand your ‘tacit theories’ – to surface them so you can critically examine them and understand if they are fit for purpose. Its also important to be able to increase the number and type of ‘methods’ you have available and to be able to adapt them to different situations – because, let’s face it, if your only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

There is some read across between ‘behaviour change’ and ‘practice development’ ideas in that they both draw into focus how the environment/ context/setting matters. As Ison says – an individual can’t be responsible, can’t develop if they are not in response-able circumstances. To go back to public health for illustrative examples, we need an emphasis on the importance of easily available, affordable healthy food – not just in telling someone they should eat five a day. And, we need to recognise how psycho-social stressors at work or in society in general can lead to people seeking relief through alcohol or smoking – it’s not enough to tell them to be ‘resilient’.

In an organisational setting, individual practitioners – whether leaders, managers or others – need to be in a setting free of constraints to innovation, trying things out – they need to be able to reflect on and think about what they are doing – they need to have opportunities to surface and test their theories – and they need their managers to coach/mentor them to develop the reflective practice mind-set. This needs to be so much part of the organisational culture that colleagues help each other in their reflective practice. And in an ever changing world, this is a continuous process, not a one off change.

Incognito in Rome recently wrote a blog that reminded me of another part of Ison’s work. He created a list of verbs that are associated with managing – such as understanding, coping, controlling, helping, delegating. As he made sense of the list, he noticed they formed into three groupings which he called (1) getting by (2) getting on top of and (3) creating space for. He explained this as follows:

‘Getting by’ could be seen as those activities devoted to personal maintenance, activities that might be exacerbated or lost with different work-life balances

‘Getting on top of’ could be seen [as] a resort to command and control procedures associated with hierarchical management or […]

‘Creating space for’ could be seen as delegation [or] could be seen as creating the circumstances for emergence and novelty (innovation) through self-organisation and removing barriers to others being responsible (i.e. creating response-able circumstances)

Ison (2010, 187)

To me, the notion of ‘behaviour change’ feels like an extension to the management repertoire associated with ‘getting on top of’. Whereas, ‘practice development’ could be seen as part of a new way of managing linked to ‘creating space for’. I know what I’d prefer to be part of.

References

Ison, Ray (2010) Systems Practice: how to act in a climate-change world, Milton Keynes/London, The Open University/Springer Publications.