One of the threads of academic discourse I have accrued papers on as I have been doing the ‘literature reviewing’ work referred to in my last post is that of “collaborative governance” – a recurring theme in public administration theory and research. As my first in-road, I decided to read the most recent paper in my list – I figured that the new stuff will build on the shoulders of the old stuff so even if I don’t feel particularly inspired by the new stuff – at least I have a feeling of the names of the people who write about this stuff. So the top of the pile (that is speaking figuratively, coz it’s all electronic) was a paper published in January 2012 (a year ago) by Emerson et al – called “An integrative framework for collaborative governance”.

It took a while to get used to the language – lots of familiar words, being used with particular nuances. I read it, read it again and then started realising just how helpful it is to me in my work (yes, distracted from my journal article per se but nevertheless useful and interesting). Perhaps it is the ‘integrative’ nature – in that it pulls on a wide range of other writing. Perhaps it is the ‘framework’ side – hey, I love a theory, particularly one that comes with a diagrammatic conceptual model. But I feel I’ve come across a gem.

Perhaps it is worth starting off by saying a little by what seems to be meant by the term ‘collaborative governance’ and why it has gained significance in academic discourse. Emerson et al do mention a number of explanations put forward by others, but then provide their own (which I really like for its breadth):

the processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished (page 2)

They remark that collaborative governance is more than just an object of study in that some authors imply it is a whole new paradigm for public administration – a big shift away from New Public Management. As someone who coordinates and develops partnership working for a living, I can think of a ‘partnership’ as a manifestation of collaborative governance (one of the structures), but more than that theory about collaborative governance is relevant to thinking differently about understanding and acting to improve partnership working.

So that set me off on a little systemic inquiry – what does the lens of collaborative governance add to my understanding of partnership? Or more specifically, placing it in my work context and drawing on Emerson et al’s framework – what do I learn about Newcastle’s Wellbeing for Life arrangements if I think of them as a collaborative governance regime? (trying desperately to avoid reification, but to use the framework heuristically to help me make sense of my messy world).

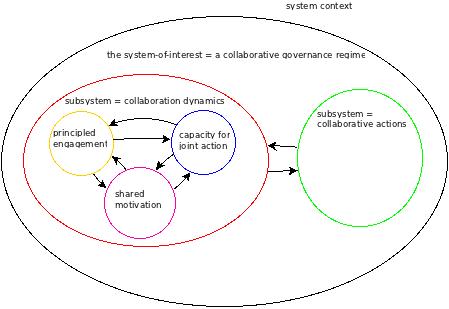

So let’s go to the article…it’s long – maybe this will be more than one blog post…no idea at this point. The integrative framework is very ‘system-like’. Emerson et al use the representation of nested 3-D boxes, cogs and arrows. I’ve decided to re-represent the model in diagrams from my systems practice – influence diagrams – noting that what gets lost in doing so is the nature of flow, dynamism and sense of process that exists in the original (just have to bring that out in my explanations).

Figure 1: An influence diagram showing the elements that give rise to a collaborative governance regime (after Emerson et al, 2012)

We’ll start with the system context. This is as you’d expect – the sort of things you would list in a PESTLE analysis or the like – political, environmental, social, technological, (eek forgotten the others) context within which the collaborative governance regime (this could get boring so henceforth CGR) exists. The context isn’t neutral – it can both offer opportunities for the CGR and constrain it’s activity.

So my system-of-interest for the purposes of my systemic inquiry is the collaborative governance regime that is concerned with improving wellbeing and health, and reducing inequalities in health in Newcastle. The system context is the English/UK government and policy – a demographic that is ageing and has inequalites – and the nature of governance of the NHS, local authorities etc.

Emerson et al draw attention to the fact that distinctive drivers for the collaboration emerge from the general systems context – without any distinctive drivers, a CGR wouldn’t be initiated (in their diagram, the drivers are a block arrow – crossing the system boundary). Thinking of the way Emerson et al explain the drivers to the ‘initiation’ of a CGR, I realise that I can’t remember a time in Newcastle where there hasn’t been something there – in the 1990s was the Newcastle Health Partnership; then the Wellbeing and Health Partnership (a subset of the wider Local Strategic Partnership) and now there is Wellbeing for Life. So I am not sure about the distinctive drivers at the beginning other than the fragmentation caused through commissioner-provider splits and emerging policy pushing partnership working and health action zones. But I can be clear of the key system context event that led to the recent “re-initiation” or reincarnation! The national election that led to the Health and Social Care Act 2012 – which in April 2013 will create new institutional arrangements for the NHS; give local authorities leadership role for public health; and, crucially require local authorities to establish statutory Health and Wellbeing Boards. These national changes did lead to ripples locally – it allowed people to express dissatisfaction with the way in which partnership working for wellbeing and health worked (it didn’t really) and start to have new conversations with the new participants.

So whilst Emerson et al talk of the specific drivers in terms of the way they create impetus for a CGR to be initiated – I guess I find it easier to think of how the drivers have perhaps caused a new ‘shake-up’ in a CGR that was kind of there before – this means there is path-dependency, what is possible is in part defined by the history. In some ways there was a choice to be made – respond to the new national requirement by re-naming what we had and carrying on as we did before with a few different faces or use this opportunity for something really new. Newcastle went with the latter. Emerson et al identify four “essential drivers, without which the impetus for collaboration would not successfully unfold” – namely leadership, consequential incentives, interdependence, uncertainty. (page 9). Some of these had been around before, we’d acknowledged for a long time the interdependence between organisations and uncertainty involved in improving wellbeing and health. But the new kicks were – a change in leadership – we had a local election which led to a new administration for the council bringing not just new priorities but also a cabinet that wanted to do politics, policy and collaboration differently and – a change in consequential incentives – the reality of an ageing demographic, greater health inequalities and a smaller budget have really kicked in, it’s really staring people in the face. These brought about a new beginning. But, I think there was something else there too, something Emerson et al don’t mention – there was a new feeling of moral obligation or ethical imperative – the realisation that this wasn’t purely a matter of organisations being able to meet ‘their’ aims better, it was a matter of human rights, a matter of people’s lives.

The other reflection I have about the drivers is that they seem to flux in terms of the awareness and urgency they give to people’s behaviour – that is probably not about the drivers themselves, more about the perceptions of the people involved. Sometimes, there seems to be this overwhelming feeling of ‘surge’ as the drivers are uppermost in people’s minds; other times it is more of a ‘lapping’ as they focus on other things.

So we’ve thought about the context and how it gives rise to our CGR, through the mechanism of the drivers. Now it is time to look inside the CGR itself. There are two primary components (I’ve called them sub-systems in Figure one up above) that make up the CGR – collaborative dynamics and collaborative actions. They do influence each other but in quite different ways. The collaborative dynamics are a pre-requisite for the collaborative actions (don’t get the actions without the dynamics) but in turn the actions give rise to impacts that may change – or require the active adaptation of – the dynamics. This relationship can be mutually reinforcing – a virtuous circle – if you get it right.

The collaborative dynamics is where it all happens really. Emerson et al view the dynamics as iterative and cyclical interactions – with three interacting components – principled engagement, shared motivation, and capacity for joint action.

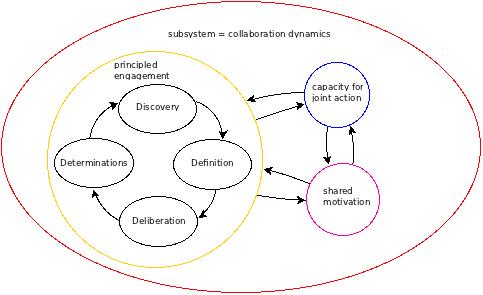

To start with we’ll bring principled engagement to the fore.

Figure 2: An influence diagram focussing on the component of ‘Principled Engagement’ and its four basic process elements

Principled engagement is a process – it takes place over time, not at a point in time. It’s about what happens in all those meetings, off-line corridoor chats, conferences etc. It’s through this process that participants create value. Why ‘principled engagement’ – this is what Emerson et al say:

“We call this component in our framework “principled” engagement to adhere to the basic espoused principles articulated broadly in both practice and research, including fair and civic discourse, open and inclusive communications, balanced by representations of [different interests], and informed by the perspectives and knowledge of all participants” (page 11)

Now, we have to think of what we term ‘participants’ in this context. Emerson et al emphasise that it can apply at small and large-scale levels. This is where I have a bit of a problem – it seems easier to apply these ideas to a ‘contained’ group of people – such as the Wellbeing for Life Board. It seems harder to broaden them to apply to ‘everyone’ who lives or works in Newcastle who has, or could have, a part in improving wellbeing and health. The job of engagement and also the job of creating any sort of shared ‘rules’ and theory of action across so many people with differing interests, values and ideas just seems too big. Sometimes this is difficult maintaining this across the Board and one or two sub-committees – even when there is some membership in common. So at what point can a CGR include so many participants that it makes it unmanageable or fragmented? I wonder whether it would be helpful to bring in ideas of recursion from the viable systems model here – where a broader level CGR provides the system context for smaller ones on a recursive basis. Or, Wenger’s discussions of a ‘community’ of ‘communities of practice’….food for thought.

The four basic processes within principled engagement (shown in Figure Two above) are Discovery; Definition; Deliberation; and Determinations. I love these processes – they resonate so well with ideas of social learning and they seem so much more like reality than normative policy or strategy models like Assess-Plan-Do etc – it is that sort of conceptualisation that has informed the Health and Social Care Act requirement that Health and Wellbeing Boards oversee an assessment of the needs of the population and then formulate a strategy. In Newcastle, we’ve endeavoured to avoid a literal interpretation of this national requirement – and in retrospect I can really see the way our Wellbeing for Life Board (Newcastle’s name for its statutory Health and Wellbeing Board) has ebbed and flowed through these four ‘D’ processes since it formed in December 2011. There has been a lot of Discovery – sharing what is important to each other; fact-finding – in particular through the ‘Know your city’ population profile. There has been Definition work – around shared language and ‘conceptual’ frameworks; thinking about what can be achieved together. Recently, I’ve seen a shift into ‘Deliberation’ where people have felt safe enough to perhaps challenge each other and have more tricky conversations, including airing ‘elephants in the room’. And then very recently, as we are getting to the point when a strategy document does has to be written, more distinctive ‘Determinations’ – agreement on what work to do together. In some ways it seems that a whole year is a very long time to get this far but on the other hand, these aren’t a group of people who are with each other all the time, they’ve formally met as a whole Board something like six times – 18 hours max of time dedicated to trying to move this forward. As pace has gathered and relationships formed, there has been more off-line meetings between smaller groups of stakeholders – perhaps these are safer places for the tough Deliberations – outside the formality of a public meeting?

Principled engagement creates and reinforces both of the other components of collaboration dynamics – shared motivation and capacity for joint action – but once created these other two components reinforce principled engagement.

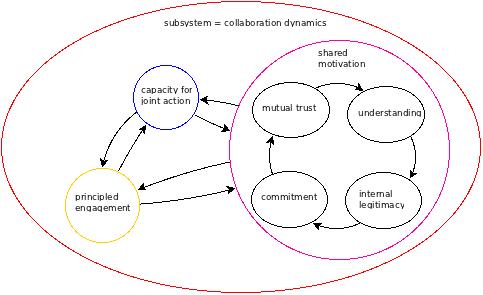

So now let’s bring shared motivation to the fore…

Figure 3: An influence diagram focussing on the component of ‘shared motivation’ and its four elements

As you can see, once again this is a self-reinforcing cycle of four elements – but not processes this time, more like ‘states’. Shared motivation intends to bring into focus the “interpersonal and relational elements of the collaborative dynamics” (page 13).

It all starts with ‘trust’ – something that you read and hear about all the time when in the world of partnerships. Trust comes about as people work with each other over time – and yes, I can see that happening in our new arrangements. You can see it emerging as people cease feeling ‘let down’ by other partners and people. I think this is an area where people have worked hard recently to ‘prove’ they are trust-worthy – in the ‘old world’ there was more suspicion and mis-trust. Alongside this is the growth of ‘mutual understanding’ referring to “the ability to understand and respect others’ positions even when one might not agree” (page 14). One of the things I have witnessed is a lessening need of people to keep repeating their own position, as if they’ve begun to realise that the others not only know that position but respect it. It means the conversations are less repetitive and can then move forward. This leads to ‘legitimacy’ – a kind of permission that it is okay to spend time in this collective endeavour – the fact that it is ‘real’ work rather than just a ‘talking shop’. And finally, on to ‘commitment’ to a shared path, rather than the separate paths of different organisations. In thinking about these two latter elements, I feel as if we are on the ‘brink’ of them emerging – I feel really hopeful and optimistic about this. I’m not sure what it is exactly that I am looking for but I think I’ll know when they are there – it seems like we are so close. The dilemma for me – in my sort of role – is that I can not create an ‘action plan’ to create commitment, I can only keep on contributing to creating the conditions where it is likely to emerge – and if I draw from this framework I think that means creating the right sort of setting and conversations for principled engagement to take place.

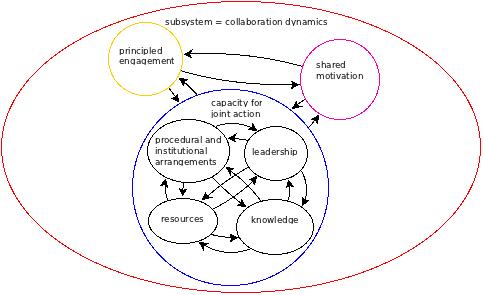

And that brings us on to capacity for joint action….

Figure 4: An influence diagram focussing on the four elements that give rise to capacity for joint action

Capacity for joint action can be understood through looking at four interacting elements – each of them generated by each other and through principled engagement and shared motivation. Without any sort of capacity for joint action, you won’t get joint action – and let’s face it joint action is the whole point of the CGR in the first place.

As a bit of an aside here – at the beginning of this section Emerson et al introduce the term ‘theory of action’ but don’t really explain it. This is not something I have heard of before but am quite intrigued by it. Here it is in context:

The necessary capacity building is specified during principled engagement, derived from the participants’ explicit or tacit theory of action needed to accomplish their collaborative purpose, and likely to be influenced by the scope and scale of the group’s objectives and activities. (page 14, my emphasis)

I get the feeling that theory of action is the participants’ understanding of what it is that needs to be done to improve the situation they are concerned about. If that is the case it seems similiar to the term ‘theory of change’ that seems to be hitting the evaluation literature. Wellbeing for Life’s theory of action seems to be implicit in the strategy as it is being written. That to reduce inequalities in wellbeing and health, and improve wellbeing and health for all, there needs to be two broad areas of action. Firstly to improve the conditions in which people are born, grow up, live their lives and grow old – effectively tackling the social determinants of health. And secondly to strengthen the impact of services – effectiveness, quality and cost. So I think we are getting there.

The procedural and institutional arrangements are about the structures and process protocols the collaborators establish to put their relationship on a formal-ish footing. This is where things seem a bit back to front in that national requirements define our primary structure for us (the statutory Health and Wellbeing Board) – sure there is some flexibility but it seems the context imposes on us a particular structure that may constrain what is possible. I think this is where Newcastle departed a bit in that it didn’t want to just do what the statute said and has endeavoured to think outside that box…hence the name Wellbeing for Life. We’ve also developed some things locally – Terms of Ref; Code of conduct; there is a Memorandum of Understanding in development; and of course the agreement to work to a single cohesive policy process called the Newcastle Future Needs Assessment. There are also current discussion about possible other structures needed to implement the strategy once developed – not just formal committees but action networks for example.

I like the way that Emerson et al discuss leadership – more as a range of roles that may be needed, rather than the usual decision-taker model.

These include the leadership roles of sponsor, convener, facilitator/mediator, representative of an organization or constituency, science translator, technologist, and public advocate, among others. Certain leadership roles are essential at the outset, others more critical during moments of deliberation or conflict, and still others in championing the collaborative determinations through to implementation (page 14)

I can see some of this coming to the fore in what is going on – and the fact that individuals are beginning to draw on different roles at different times – for example, one minute a representative of their organisation, the next a public advocate. Thinking of my role, in developing, coordinating and supporting the arrangements I can even see myself in there as ‘facilitator/mediator’ as well as a ‘championing’ role and ‘science translator’ – and not mentioned here ‘policy translator’.

Onto knowledge and again explanations that really resonate with me, especially because of this citation that is included:

“‘‘Knowledge is information combined with understanding and capability: it lives in the minds of people . . . Knowledge guides action, whereas information and data can merely inform or confuse’’ (Groff and Jones 2003)” (page 15)

So often we spend tons and tons of time on pulling data together to re-present it in different ways, as if manipulating the numbers and reading them again and again will somehow give some sort of magic solution. The idea that you have to engage with data – give it context in your heads – and then take responsibility for letting it guide your action, alongside theories and ideas about how the world works, is so much closer to the notion of embodied knowledge included in my Systems studies. I think we do have a growing knowledge ‘pool’ – both individual and shared – in our arrangements, however I am not certain that we yet value the need to draw on that knowledge, as opposed to reading data and facts.

And onto the fourth element – resources – which could be lots of different things that the collaboration needs to function both in terms of its ‘internal’ needs and in terms of achieving its public purpose. Again I think we are currently poised on a cliff – there are some obvious resource – like me for example – that people understand belong to the collaboration. But others people still see as belonging to the constituent partners – particular technical expertise, for example. This could go one way or another – will people realise that ‘letting go’ of owning resources can end up leveraging greater potential if they are put to work in support of the collaboration. I hope so.

So we’ve now spent ages focusing on one element of the CGR – namely the collaborative dynamics. The other element (do you remember ages ago in Figure one) is collaborative actions. As mentioned before, the collaborative dynamics are a necessary pre-requisite for collaborative actions. But it is actually the collaborative actions that we want – we want people to do something about the situation they are there to improve. Some of the actions may be things that impact on collaborative dynamics (e.g. from my current work is developing a Memorandum of Understanding) but other actions are the things intended to impact on the situation that we were set up to improve in the first place i.e. the wellbeing and health of people in the city. This is how the CGR impacts back on its system context. I like the way that Emerson et al allow for a huge breadth of actions:

Collaborative actions may be conducted in concert by all the partners or their agents, by individual partners carrying out tasks agreed on through the CGR or by external entities responding to recommendations or directions from the CGR (page 17)

As our strategy is being written, I can see the need to shape it so that it allows for these different sorts of action. It’s like some sort of venn diagram – there are some things a partner can just get on with and then tell the others, there are other things that you need to take every step together.

In addition to discussing impacts of actions – Emerson et al discuss adaptations to those impacts, whether that is adaptations to the collaborative dynamics or the collaborative actions. This draws attention to the need to learn and respond quickly to what has changed in a dynamic world – rather than carrying on doing what you wrote in a formal plan months ago, just because you said you’d do it. I agree with this – but I think it is still hard to do when a lot of the ‘requirements’ tell us to ‘write and deliver a strategy’. These sorts of tools make us assume certainty and predictability and perhaps take our eyes of the need to learn. It remains to be seen whether we can avoid this trap.

Emerson et al end their article by discussing the whole framework and suggesting how it can guide future research priorities. For me, my systemic inquiry should end up with some sort of ‘so what?’. I’ve certainly found the framework valuable to understand my world but I am not sure at the moment whether this new understanding (knowledge) will guide different sorts of actions than I would have taken before. Perhaps in some ways, I have discovered additional conceptual material that reinforces what I was doing/what I thought anyway – that could make me more determined. Maybe the causal pathway from reading the article and writing this blog to the actions I take won’t be that linear and attributable. Nevertheless, I think it has been a valuable exercise.

All one post afterall – but it did take me three days.

References

Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T. & Balogh, S., 2012. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1), pp.1–29.